Mexico never stops surprising me. All it takes is stepping off the main roads to find yourself in a world of stories — small and large — that deserve to be told. It was no different when my friend and colleague, photographer Ricardo Vidargas, invited me to visit San Isidro, a small village about 25 kilometers from San Miguel de Allende. You can only reach it on foot, on horseback, or with a solid 4×4.

We set off — and got lost several times. With no internet connection, we ended up using a drone to figure out the route.

In those 25 kilometers, we met only one person: a woman who stopped to talk with us and invited us to have lunch at her home, hidden somewhere in the green hills. This is something I’ve always found remarkable in Mexico — and more broadly in Latin America: despite everything, people are not afraid. The instinctive response to a stranger is still one of trust and welcome. We politely declined but exchanged phone numbers.

The landscape was breathtaking. The air was filled with butterflies, some of them huge — unlike any I’d seen before. Along the way, we passed small roadside chapels where Catholic and animist traditions coexist, layered together without contradiction.

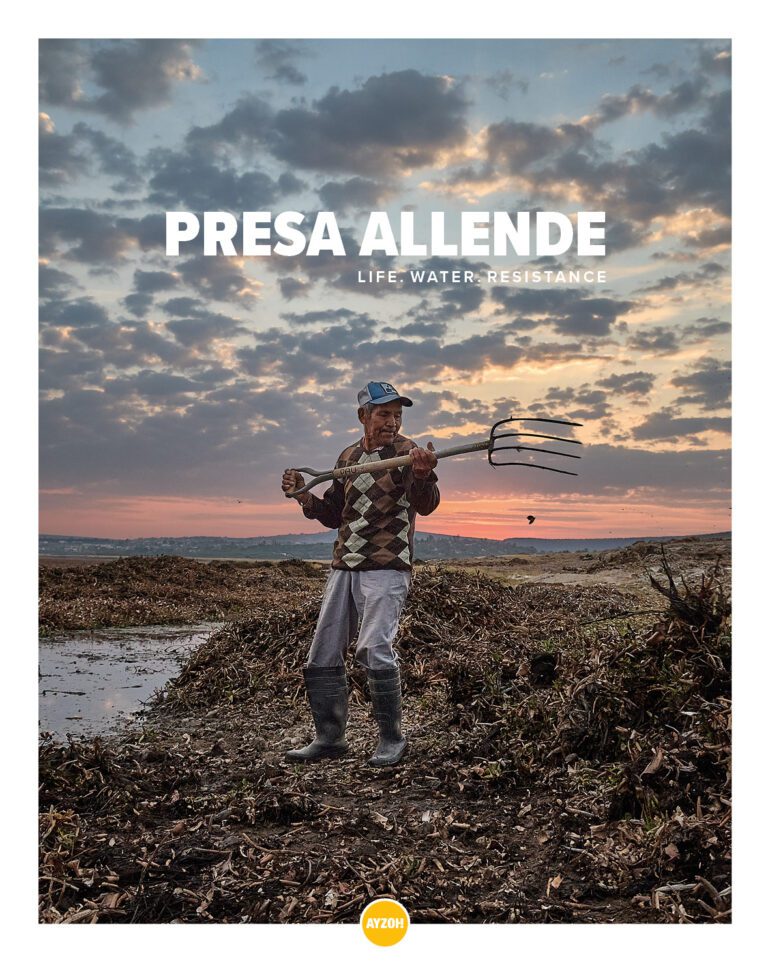

San Isidro is made up of about twenty homes, a tiny shop, a kindergarten, a primary school, and a secondary school — 25 students in total. There we met Federico, a 70-year-old man who has lived in the village his entire life with his wife and sister. They farm the land — mostly corn — and take care of the local water reservoirs, which are vital for the animals that roam freely through the valley.

They welcomed us with the usual phrase: “Nuestra casa es su casa.” This time we didn’t say no — polite, yes, but not foolish: in Mexico, food, whether humble or refined, is almost always incredible. And this was no exception.

After lunch, something unexpected happened.

Federico’s land is part of the Cañada de la Virgen, a canyon that was once a major pre-Columbian settlement. Although he never attended school, Federico has developed a deep passion for archaeology. As we walked through his seven hectares of land, it was clear how much care he puts into every corner — every plant, every insect, every stone.

There are hardly any rocks scattered on the ground, because over the years, Federico has gathered them all — literally tons — and arranged them into low dry-stone walls that are like open-air museums.

Walking with him, it feels like he’s in conversation with the stones. He tells us what each one means: an amphora, an arrow, a grinding slab, the foundation of a home… And he tells it with such clarity that you can almost picture the people who once lived here going about their lives.

Then the rain started, and we had to leave. But I know we’ll be back.

Federico is one of those people I quietly add to a personal list — my own version of the “righteous”, like in Jorge Luis Borges’ writings. People who, without knowing it, are keeping the world together.