Yesterday in Rimini, two protests against the war in Ukraine took place. One was held under the Arch of Augustus, organized by political parties and associations. The other gathered quietly at the Tiberius Bridge, called by the local Ukrainian community. We were there with our cameras. We were asked to write something. We won’t.

Not out of detachment, but out of respect—for the complexity of things, and for the limits of our voice. Instead, we prefer to let the images speak. Here’s why.

First: As photographers, we’ve witnessed the consequences of war. But we’re not war experts. Our job is to observe, document, and present what we see—never to pretend we understand more than we do. There’s no such thing as full objectivity, but there’s such a thing as honesty.

Second: As people, we were disturbed by many of the speeches we heard. Words that sounded like performances. Politicians hungry for a stage. Simplistic geopolitical sermons in the face of real human loss. It would have been better to kneel. In silence. Letting the wind that swept through Rimini say what needed to be said.

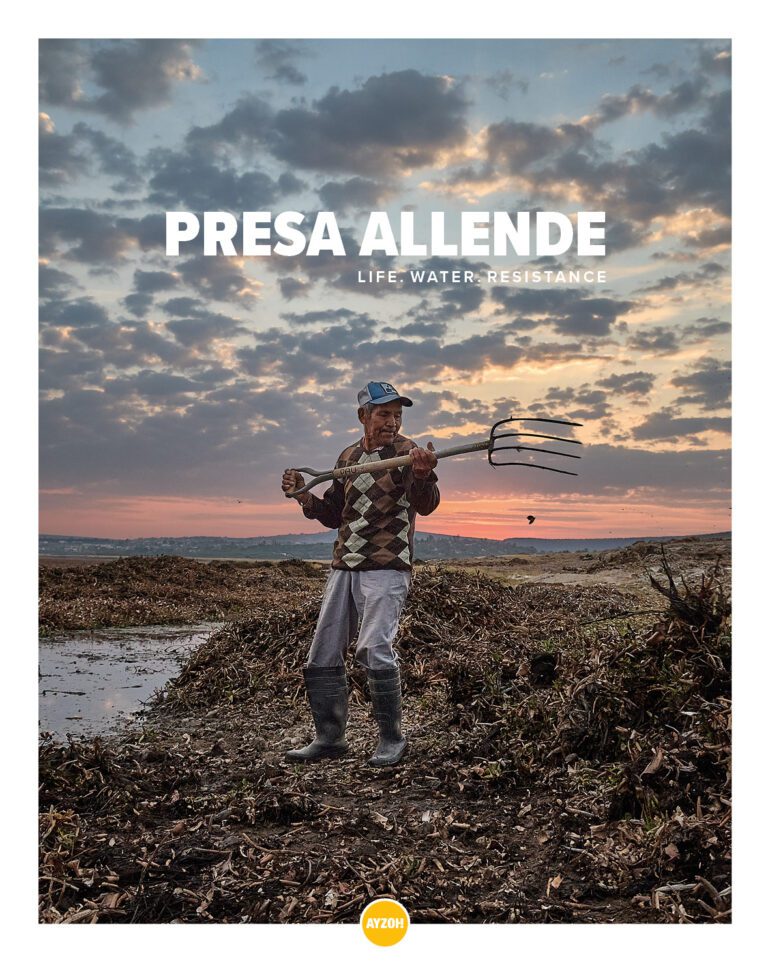

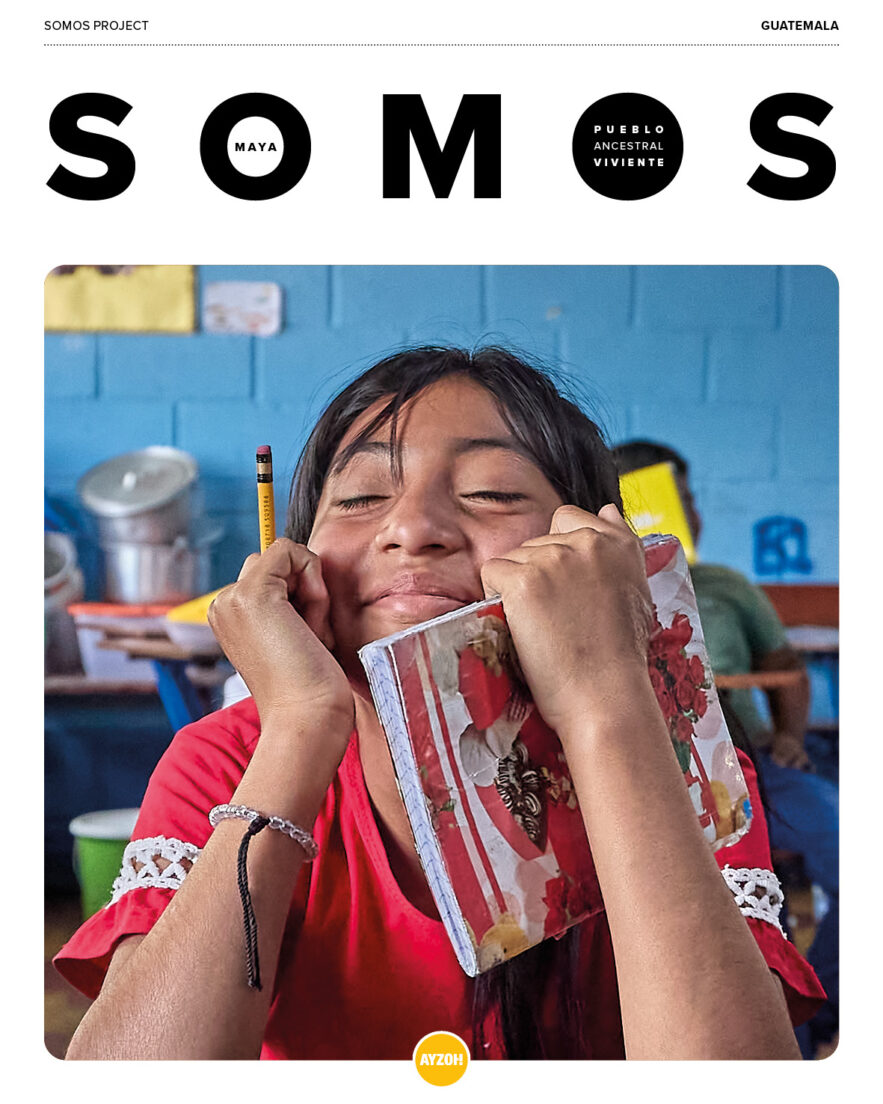

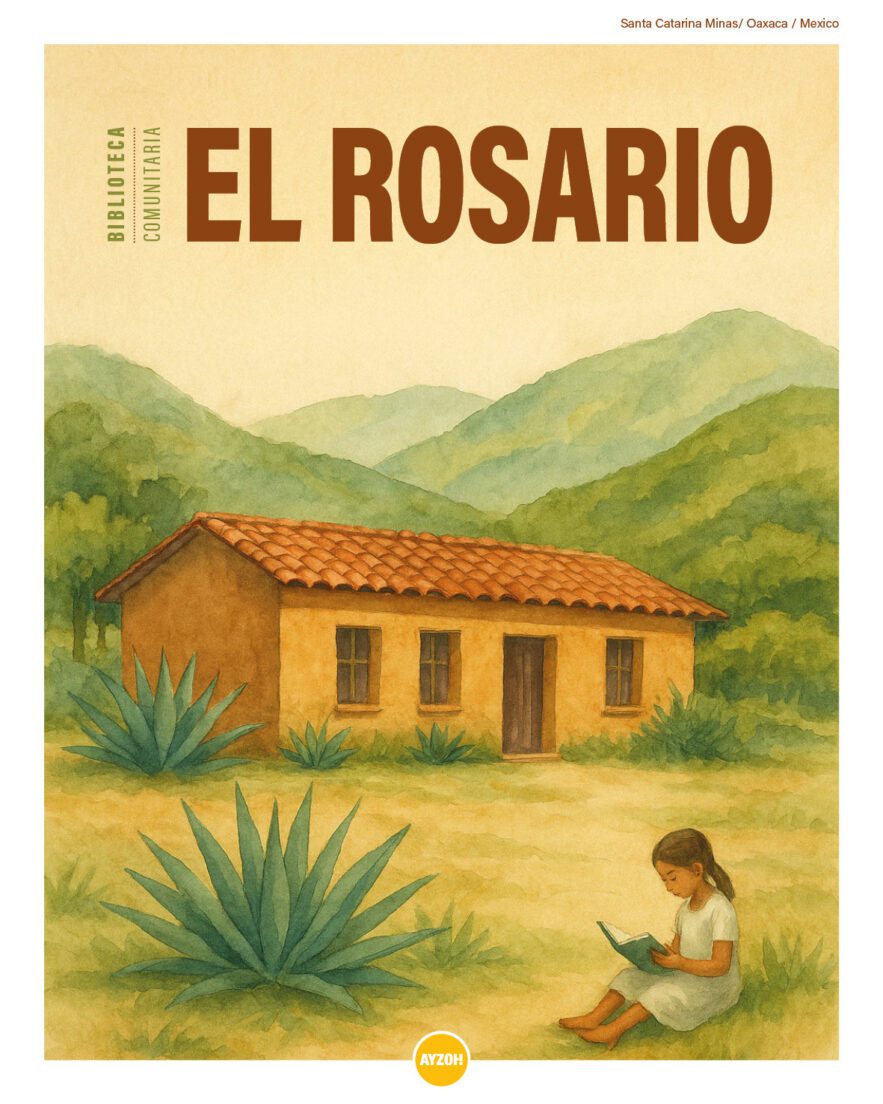

Third: As Ayzoh!, we are committed — by statute and by choice — to telling stories that build bridges. We work with communities across continents to document everything that strengthens the idea of a common home. We stand against anything that divides: flags (when they become walls), borders, the glorification of war. And so, against all war.

That’s why, today, we choose not to write a report.

Instead, we reprint below a speech that speaks for us. A speech we make our own. Delivered by Gino Strada—surgeon, founder of EMERGENCY, and lifelong witness to the devastation of armed conflict—at the Right Livelihood Award in Stockholm, 2015. His words are as relevant now as they were then. Maybe even more.

Gino Strada’s Speech

Honorable Members of Parliament, Honorable Members of the Swedish Government, Members of the RLA Foundation, Fellow Award Winners, Excellencies, Friends, Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great honor for me to receive this prestigious recognition, which I consider a sign of appreciation for the exceptional work carried out by the humanitarian organization EMERGENCY over the past 21 years, in favor of the victims of war and poverty.

I am a surgeon. I have seen the wounded (and the dead) from various conflicts in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and Europe. I have operated on thousands of people wounded by bullets, bomb fragments, or missiles.**

In Quetta, the Pakistani city near the Afghan border, I first encountered the victims of landmines. I have operated on many children wounded by so-called “toy mines,” small green plastic parrots the size of a pack of cigarettes.

Scattered in the fields, these weapons wait for a curious child to pick them up and play with them for a while, until they explode: one or two hands lost, burns on the chest, face, and eyes. Children without arms and blind. I still vividly remember those victims, and seeing such atrocities changed my life.

It took me a while to accept the idea that a “war strategy” could include practices such as targeting children and mutilating children in the “enemy country.” Weapons designed not to kill, but to inflict horrible suffering on innocent children, placing a terrible burden on families and society. To this day, those children are for me the living symbol of contemporary wars, a constant form of terrorism against civilians.

A few years ago, in Kabul, I reviewed the medical records of about 1200 patients to find that less than 10% were presumably military personnel.

90% of the victims were civilians, a third of whom were children. Is this “the enemy”? Who pays the price of war?

In the last century, the percentage of civilian deaths increased dramatically from about 15% in World War I to over 60% in World War II. And in the more than 160 “significant conflicts” the planet has experienced since the end of World War II, with a cost of over 25 million human lives, the percentage of civilian victims has hovered around 90% of the total, similar to that observed in the Afghan conflict.

Having worked in war-torn regions for over 25 years, I have seen firsthand this cruel and sad reality and perceived the extent of this social tragedy, this massacre of civilians, which occurs mostly in areas where healthcare facilities are practically non-existent.

Over the years, EMERGENCY has built and managed hospitals with surgical centers for war victims in Rwanda, Cambodia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Sierra Leone, and many other countries, later expanding its medical activities to include pediatric centers and maternity wards, rehabilitation centers, outpatient clinics, and emergency services.

The origin and foundation of EMERGENCY, which took place in 1994, did not stem from a series of principles and declarations. It was conceived on operating tables and in hospital wards.

Treating the wounded is neither generous nor merciful; it is simply right. It must be done.

In 21 years of activity, EMERGENCY has provided medical and surgical assistance to over 6.5 million people. A drop in the ocean, one might say, but that drop made a difference to many. In some ways, it also changed the lives of those who, like me, shared the experience of EMERGENCY.

Each time, in the various conflicts in which we have worked, regardless of who was fighting whom and for what reason, the result was always the same: war meant nothing more than the killing of civilians, death, destruction. The tragedy of the victims is the only truth of war.

Confronted daily with this terrible reality, we conceived the idea of a community where human relationships are based on solidarity and mutual respect.

In reality, this was the shared hope around the world after World War II. This hope led to the establishment of the United Nations, as stated in the Preamble of the UN Charter: “To save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind, to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small.”

The indissoluble link between human rights and peace, and the mutually exclusive relationship between war and rights, were also emphasized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, signed in 1948. “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” and the “recognition of the inherent dignity and the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world.”

Seventy years later, that Declaration appears provocative, offensive, and blatantly false. To date, not one of the signatory states has fully implemented the universal rights it committed to uphold: the right to a dignified life, to work, and a home, to education and healthcare. In a word, the right to social justice. At the start of the new millennium, there are no rights for everyone, but privileges for a few.

The most aberrant, widespread, and constant violation of human rights is war, in all its forms. By denying the right to live, war negates all human rights.

I would like to emphasize once again that, in most countries ravaged by violence, those who pay the highest price are men and women like us, nine times out of ten. We must never forget this.

In November 2015 alone, over 4,000 civilians were killed in various countries, including Afghanistan, Egypt, France, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Nigeria, Syria, and Somalia. Many more people were wounded and mutilated or forced to leave their homes.

As a witness to the atrocities of war, I have seen how the choice of violence has – in most cases – brought only an increase in violence and suffering. War is an act of terrorism, and terrorism is an act of war: the common denominator is the use of violence.

Sixty years later, we are still faced with the dilemma posed in 1955 by the world’s leading scientists in the so-called Russell-Einstein Manifesto: “Shall we put an end to the human race or shall mankind renounce war?” Is a world without war possible to ensure the future of humankind?

Many might argue that wars have always existed. It’s true, but that does not prove that resorting to war is inevitable, nor can we assume that a world without war is an impossible goal. The fact that war has marked our past does not mean it must be part of our future.

Like diseases, war must be considered a problem to be solved, not a fate to embrace or appreciate.

As a doctor, I could compare war to cancer. Cancer oppresses humanity and claims many victims: does that mean all the efforts made by medicine are useless? On the contrary, it is precisely the persistence of this devastating disease that drives us to multiply our efforts to prevent and defeat it.

Envisioning a world without war is the most challenging problem humanity must face. It is also the most urgent. Atomic scientists, with their Doomsday Clock, are warning humans: “The clock now stands at just three minutes to midnight because international leaders are failing their most important duty: ensuring and preserving the health and life of human civilization.”

The greatest challenge of the coming decades will be to imagine, design, and implement the conditions that allow us to reduce the use of force and mass violence to the point of complete abandonment of these methods. War, like deadly diseases, must be prevented and cured. Violence is not the right medicine: it does not cure the disease, it kills the patient.