My work with the Burji people in southern Ethiopia focuses on documenting a language that is both rich and at risk. I am in the field for the Department of Linguistics at the University of Pavia, continuing a long-term effort to record Dhaashatee, the language spoken by the Burji communities in the highlands south of Lake Chamo.

It is one of the least documented languages in the Highland East Cushitic group, and its transmission is under pressure from migration, schooling in other languages, and changing cultural practices.

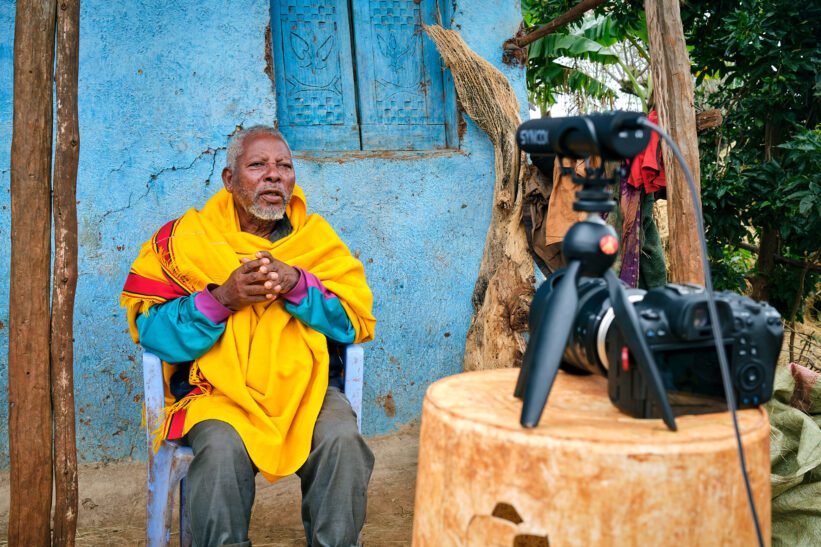

I work through direct contact. I spend time with elders, clan leaders, and families. Their knowledge is not written. It lives in proverbs, stories, and everyday speech. Much of my work takes place in courtyards, fields, and communal spaces, listening to variations in dialect, noting verb forms, and collecting examples of how people speak in daily life.

Their distinctions between highland and lowland varieties, their use of complex verb morphology, and their oral heritage add layers that written sources rarely capture.

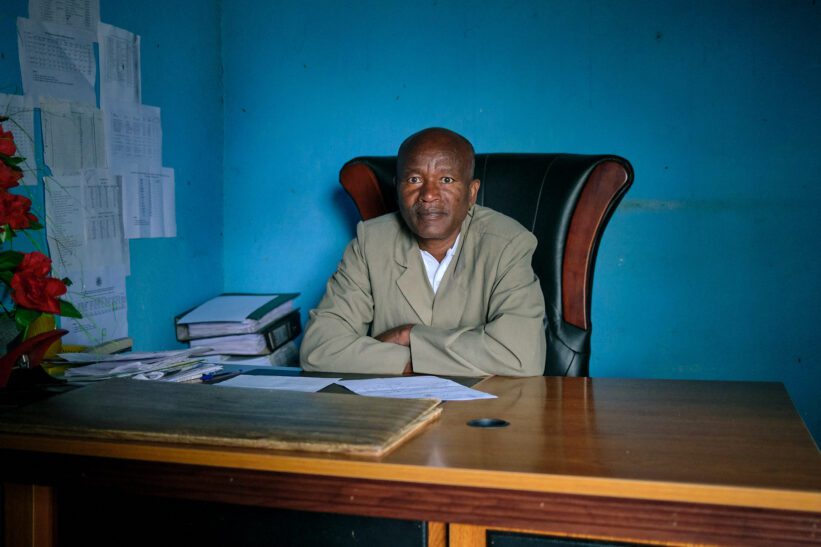

The same approach guides the photographic work. I photograph the environments where language is used, not staged scenes. Agriculture, weaving, local governance, and religious ceremonies all shape linguistic life. Many conversations take place during shared meals or while walking between villages. These moments help clarify how language and community practices reinforce each other.

The Burji also carry memories of their movements, older ties with neighboring groups, and a social order rooted in cooperation. Their history is only partially documented. Many details survive through the accounts of elders. My field notes include these narratives because they influence how people describe themselves and their place in the region.

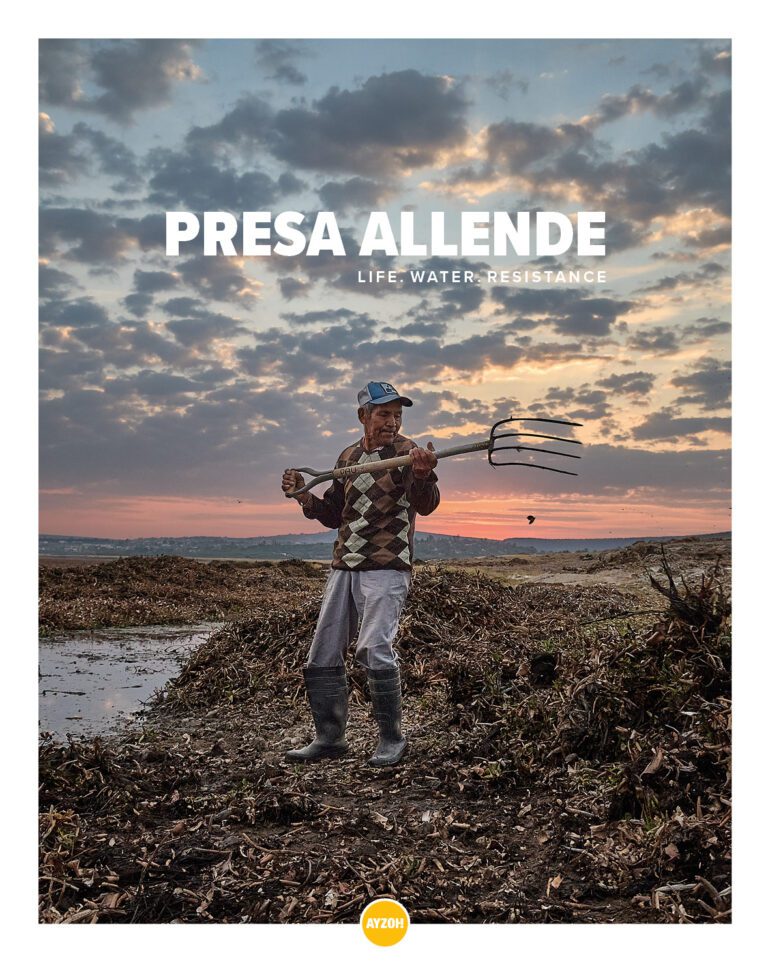

This work is slow and depends on trust. The goal is to produce accurate linguistic data, visual documentation, and a record that supports future research. The material collected will contribute to a book developed with Ayzoh!, built on shared fieldwork and long stays inside the communities.

For the Burji, language is not an artifact. It is a living system that connects people, land, and memory. My task is to document it with care, before more of its knowledge disappears.