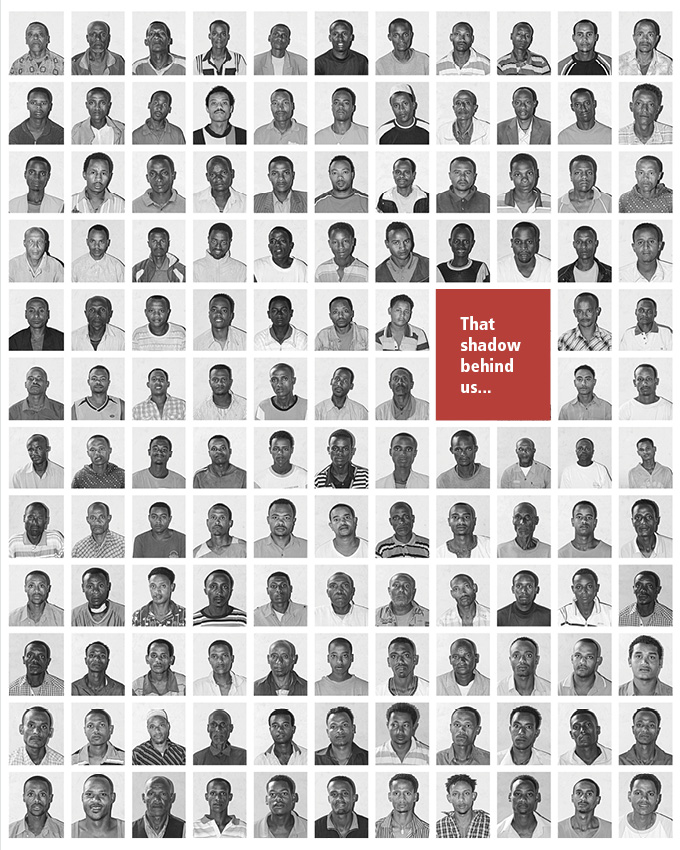

In the heart of Uruapan, in a 19th-century textile mill reborn as a cultural space, the ghosts of threads and looms have given way to another kind of weaving: one made of silver halides, memory, and light. Here, suspended from the ceiling on large sheets of woven cloth, 200 photographs by Graciela Iturbide float like apparitions. The exhibition bears no title beyond her name. It doesn’t need one.

These aren’t just photographs. They are thresholds. Portals to moments where time folds, rituals breathe, and the ordinary becomes myth. The layout itself – conceived by architect Mauricio Rocha, her son – redefines how we move through the work. The images don’t hang on walls: they hang in space. You don’t observe them. You move among them.

No Chronology, No Categories. Just Life

Graciela herself selected the images. No thematic thread. No strict chronology. Just the rhythm of a long life behind the lens. A life lived with curiosity and restraint, with an eye that watches but never intrudes.

“Everything that has surprised me in these 50 years is there,” she says. And that’s what guides the exhibition: surprise. That quiet jolt when the world, for a second, reveals its soul.

From Juchitán to Sonora, from Japan to India, from dusty birds to volcanic stones, Iturbide’s eye captures what doesn’t scream. Her photography has always been about presence, not spectacle.

The Sound of Images

There’s a soundtrack. Literally. A sound installation by Manuel Rocha – another of her sons – weaves ambient tones of water, wind, church bells, fragments of silence. It doesn’t narrate. It listens. It hovers around the images like breath. Iturbide herself admits she’s unsure what it will mean. That ambiguity suits her work. Nothing here asks to be explained.

More Than Icons

Of course, some of her best-known photographs are here: Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas (1979), Mujer Ángel (1979). But they aren’t centerpieces. They’re simply part of the story. Like pages in a book that continues to write itself.

Alongside them are newer works – never shown before – from her recent obsession with volcanic landscapes. These images, born during a residency in Lanzarote, now lead her toward the Popocatépetl, the Paricutín, the deep geology of myth.

“I’m reading Darwin now,” she says, half-smiling. “Because every project leads me somewhere else.”

An Artisan of Time

Iturbide still works analog. Film, contact sheets, darkroom. She calls photography a form of craftsmanship. She means it. She doesn’t do digital. Not out of nostalgia, but because she values the rhythm. The pauses. The slowness that lets meaning emerge.

Some of the photos in this exhibition had to be printed anew. Others were rescued from forgotten negatives. And in the process, she looked at her old work again – sometimes with love, sometimes with doubt. “There are images I see and think, why on earth did I take that?” she laughs.

The archive is not a monument. It’s alive. It grows. It argues with itself.

Against Misery, Against Spectacle

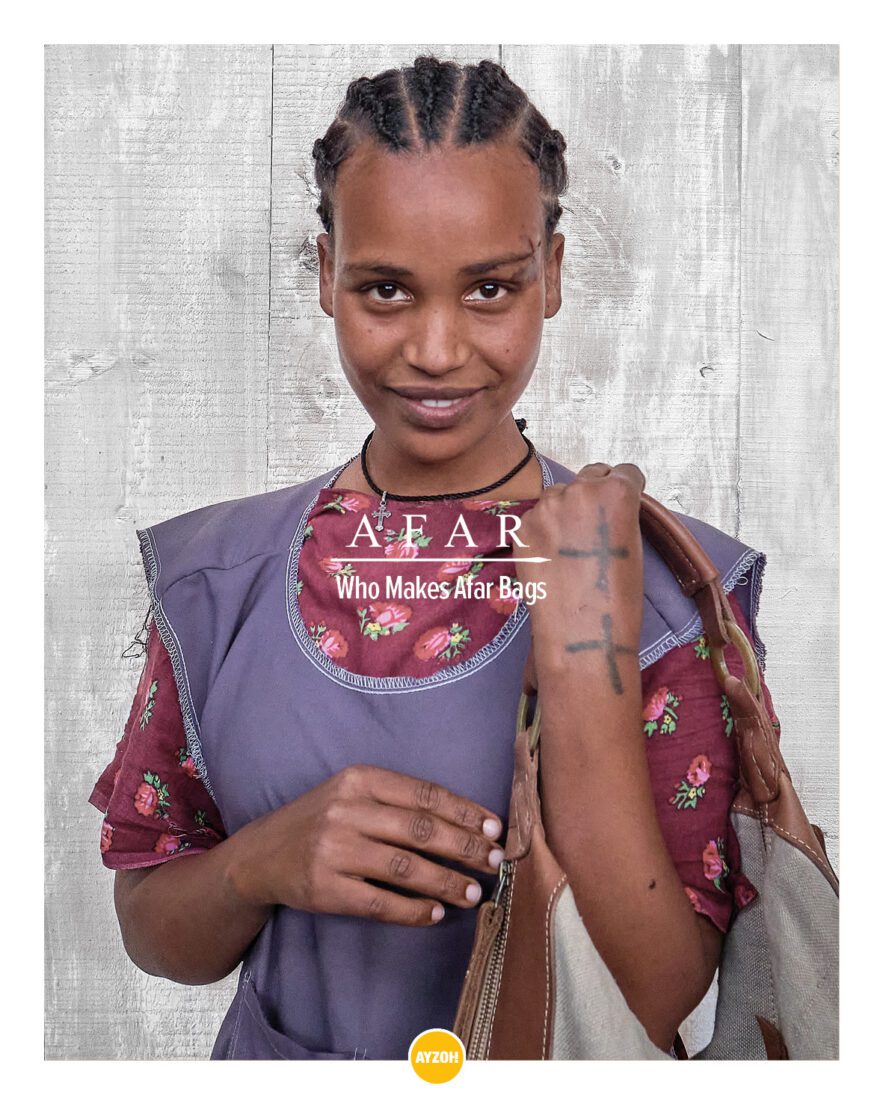

What’s missing in Iturbide’s work is as important as what’s shown. You won’t find misery porn. No sentimental poverty. No exoticism. Her portraits – especially of Indigenous communities – are collaborations, not captures.

“I avoid morbid scenes. I avoid showing poverty just for impact,” she says. The respect is palpable.

Her photographs resist labels. They are documents, yes – but also poems. They are visual anthropology without the colonizing gaze. They are fictions of truth.

Birds, Light, and a Life Without Pause

If there’s one recurring presence in her work, it’s birds. Not metaphorical birds – real ones. Flocks. Flights. Solitary shapes against bare skies. In India, in Oaxaca, in her own garden.

“Birds can fly. That’s why I photograph them. Though maybe they’re not as free as I think,” she says, half-joking, half-serious.

That tension – between freedom and illusion – runs through her entire body of work.

A Legacy That Refuses to Stand Still

Iturbide received the Hasselblad Award in 2008. She’s been shown in the Getty, the Pompidou, the Tate. But none of that is what makes this exhibition special. What matters is this: that in a textile factory once humming with machines, her images now hum with quiet power.

They don’t ask to be admired. They ask to be seen. Not analyzed. Felt.

Graciela Iturbide isn’t documenting the world. She’s inhabiting it. And she invites us to do the same – with less judgment, more surprise.