The works of Sebastião Salgado, the renowned Brazilian photographer, played a significant role in my decision to become a photographer. Yesterday, after years of studying his photographs in books, I finally had the opportunity to visit one of his major exhibitions: “Amazônia,” currently held at the MAXXI in Rome, curated and set up by his wife, Lélia Wanick Salgado.

In “Amazônia,” much like in the eponymous book published by Taschen, the over 200 exhibited photographs, captured over eight years, narrate his 48 journeys through the Amazon rainforest – the “Green Lung” of the world – in search of communities maintaining a strong connection with Mother Earth.

My expectations were not disappointed. What Sebastião Salgado presents is a true immersion into something reminiscent of earthly paradise, the beginning of humanity and life. Jean-Michel Jarre’s musical landscape, accompanying visitors along the exhibition, plays a crucial role, allowing spectators to engage with the forest through all their senses: the atmosphere evokes the smell of pipe smoke, the taste of fish, and the freshness of river water.

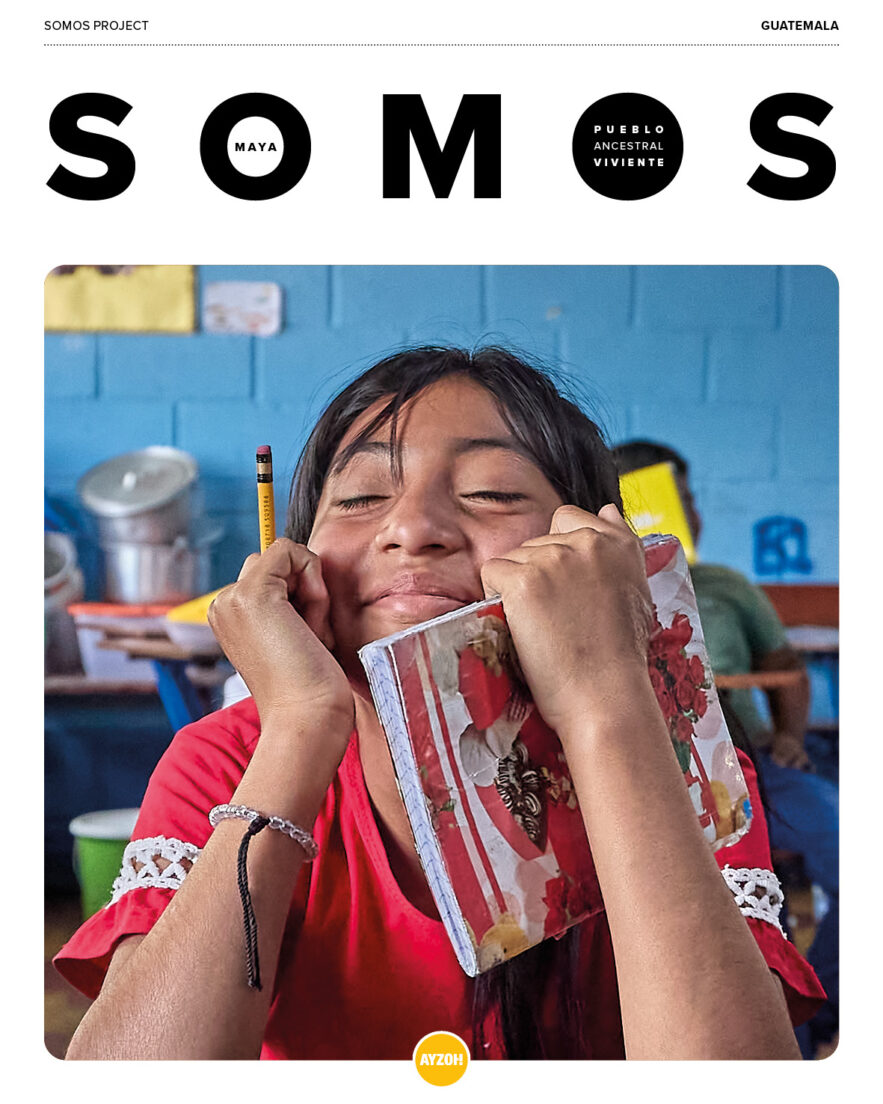

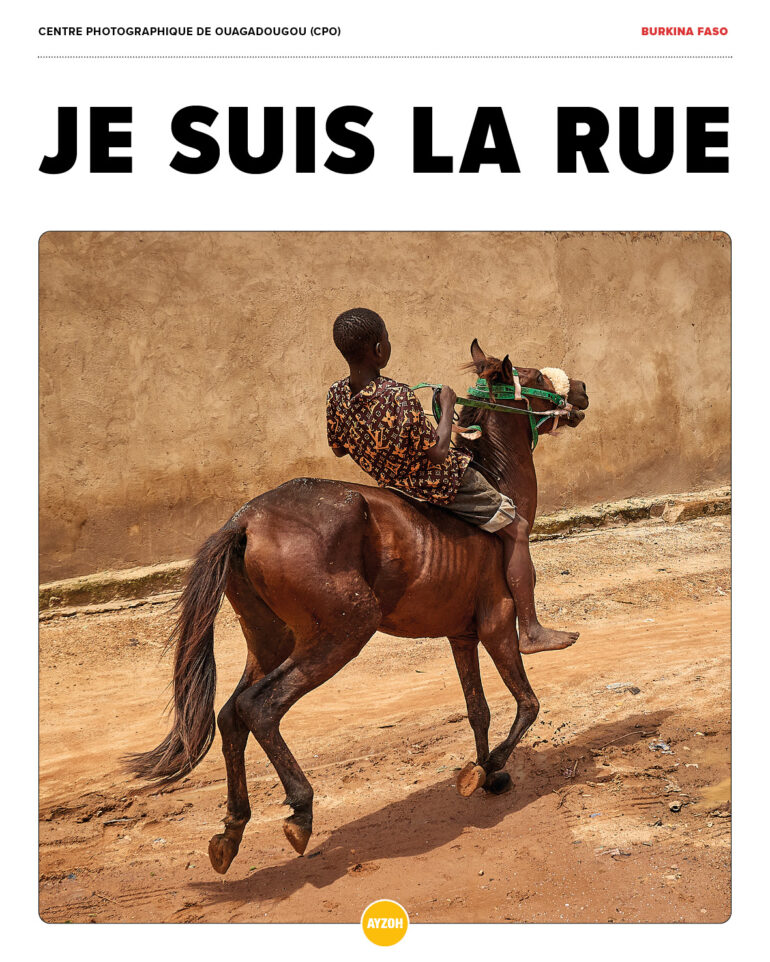

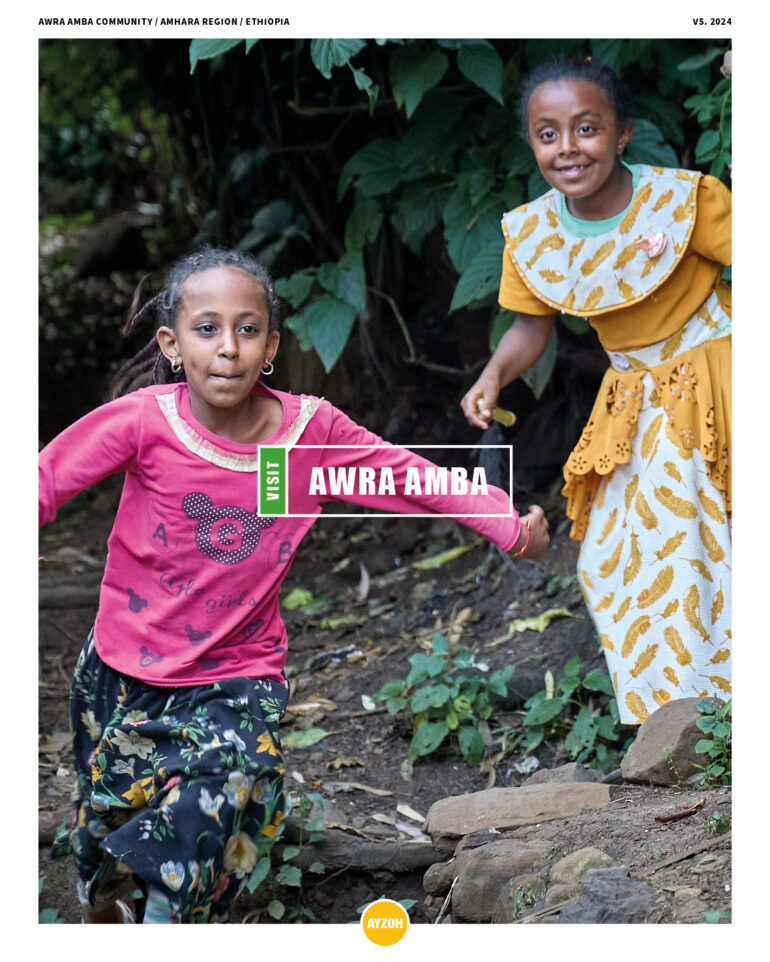

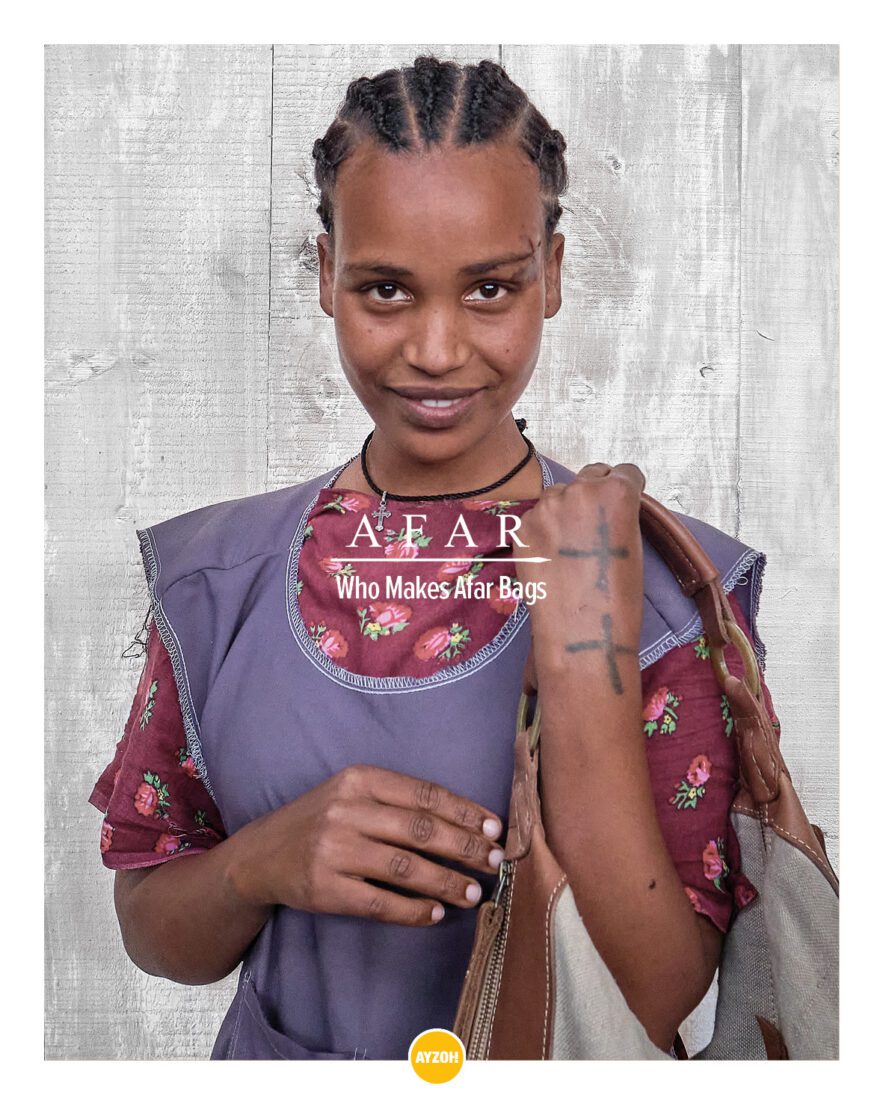

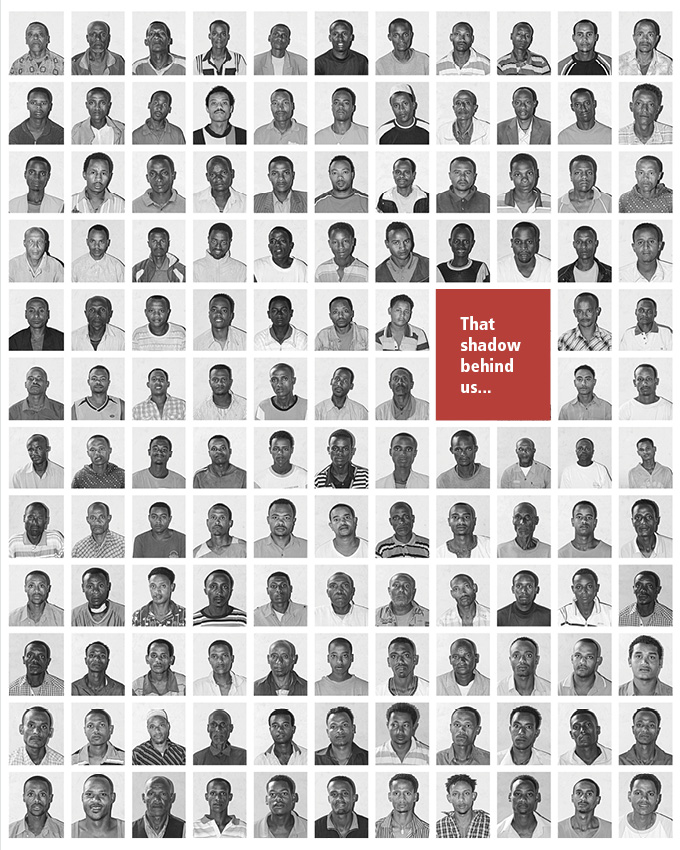

Then there are the portraits of those who inhabit, care for, and venerate the forest. Despite the linguistic and cultural barriers that separate them (which initially intimidated him), Sebastião Salgado manages to capture their strength and dignity without falling into the clichés of “poverty porn.” He communicates with them, revealing what unites us: our emotions are the same, we love in the same way, they are us and we are them.

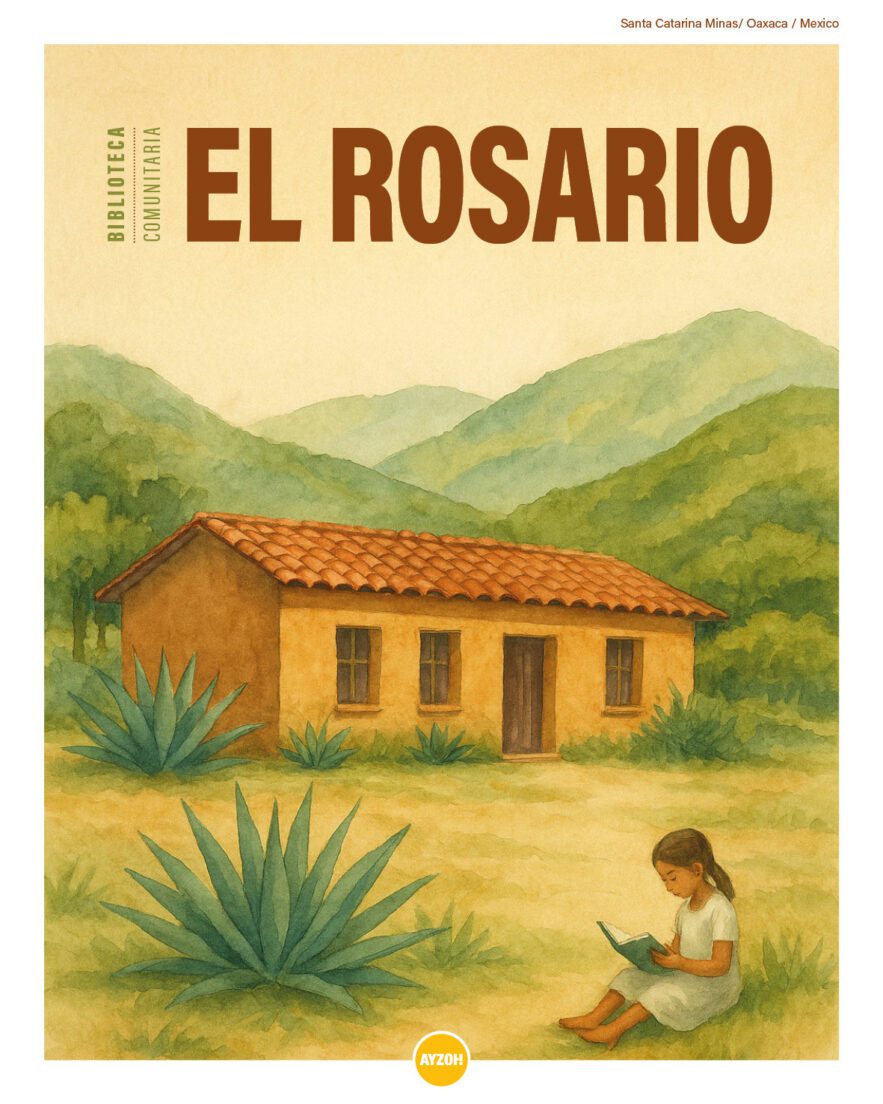

Every detail in “Amazônia” seems designed to make us relive what has been lost in other parts of the world over the centuries: the sanctity of the union between Man and Nature. Simultaneously, the exhibition resonates as a warning and a cry for help: the beauty of this planet must be preserved, not destroyed, exploited, or burned.

However, due to the beauty emanating from each image, Sebastião Salgado has been criticized for years. He is labeled an aesthete, too focused on an aesthetic search that numbs the pain and issues he denounces. “Amazônia” has even been called “a mere exercise in style,” using strongly emotional black and white photography that creates a “spectacularization of nature.” Critics argue that this “questions the ethical and anthropological value of his entire body of work.”

While I don’t fully agree with these criticisms, I, too, sensed a missing piece in the exhibition: the devastation and issues caused by deforestation are described through texts and local testimonies, but not visually through photography.

I believe the role of the inhabitants of these paradisiacal places – the people most affected by the ongoing devastation – is somewhat marginal. There are only 109 photos for ten populations, compared to the 95 dedicated to landscapes. The sizes of the prints dedicated to them are also considerably smaller than those of a more landscape nature.

Additionally, the choice to draw the viewer’s attention using black backgrounds in the portraits left me somewhat perplexed. While the expressiveness and strength of indigenous populations are powerfully imprinted in memory, the removal of the natural context can be perceived as a lack, as it is a fundamental part of their identity.

Sebastião Salgado has justified his choices in numerous interviews: as he also claims in “Genesis” – his previous project – nature is not contemplative. Nor is it indifferent to humans. Nature is a living and suffering organism, whose connection with humans can never be completely severed.

He is not interested in fueling media hunger with yet another set of tear-inducing or catastrophic images. He wants to contribute to healing the bond between humans and nature through the awe generated in those who observe his photographs. He wants to convince us that there is a paradise to protect. That paradise is called Earth.