I originally wrote this text for the Camp Erech Box — the publication we created during our time in the Mauritanian desert. It was never meant to be public, but now that the project continues to travel and evolve, I feel ready to share it here. — Giulia

Some questions we carry with us for years — never answered, never abandoned. Life moves past us, fast and uncatchable, until one day becomes an hour, and an hour a minute. Time slips like sand between your fingers. And suddenly, you find yourself lost, without coordinates, without a starting point or destination.

Where is my path leading?

Before leaving for this journey, I was afraid. Insecure. I didn’t think I’d make it. I feared the distance — not just in kilometers, but from the comforts I knew: the idle chat of an evening aperitivo, Sunday lunch at my grandmother’s. But I left.

Hours and hours in a minibus, suffocating heat, scorching winds, sandstorms that sting your skin, lightning storms that wipe out the night. In the desert, every element is larger than you. Nature reveals its power. And reminds you: one person alone is worth very little out here.

Lost in the desert, surrounded by a thousand dangers, naked between sand and stars, torn from the poles of my life by an infinite silence, I meditated on my condition. I no longer possessed anything in the world. I was nothing but a mortal among sand and stars, aware only of the sweetness of breathing… and yet I discovered I was full of dreams.

— Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

So why stay another day?

The desert gives a gift each day. Sometimes it’s the shock of cold water running down your throat, brief and blessed. Sometimes it’s the moment your feet sink into warm sand that no longer burns after a long sun-drenched day.

It might be the shared silence beneath a tree, or the sweetness of tea offered without words. It might be the night sky — endless and alive with falling stars so bright they seem to trace a map toward truth.

Red sunsets become violet dawns, the color of bissap. The footsteps of the day are erased overnight by wind, which carries off both thoughts and insects. By morning, no trace of me remains.

What am I doing here, alive, among these incorruptible marbles? I, perishable, whose body will dissolve — what business do I have with eternity?

— Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Then a girl named Minatou takes my hand. In a language I don’t yet understand, she tells me: come with me. She leads me to a mountain, and shows me a hidden engraving inside a small cave — a passage carved long ago by those who came before us.

Sometimes, between people, a primordial connection forms. Words aren’t so hard to decipher. They were my ancestors. Because of them, I’m here. Because of them, I can run, sing, dance. Because of them, I can say: I am home.

But where is home, really?

Living between one journey and the next forces you to let go of the place you grew up in — of family, of everything that once made you feel safe, but that no longer tastes like home. My mind is elsewhere — in Navissa’s drums, in the veil of Nibkoha as she dances. My body wants to reach them. I want to dance, too.

This magnetic pull toward the unknown, toward discovery and movement, sweeps me away. What once felt like curiosity has become something else — something necessary. A hunger. And that hunger ends, for a moment, when Fatimatou offers me tea and says she is my “Mauritanian mother.”

The wonder of a house is not that it shelters you or warms you, nor that it belongs to you. The wonder is that it has slowly deposited in you stocks of sweetness. That it forms, deep in your heart, the solid mass from which dreams rise like spring water…

— Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

“Am I brave, or am I running away?”

That’s a question Yahya often asks himself. And I ask it, too. But you taught me that sometimes, running is courage. I saw it in every step you took, leaning on your stick. I saw it each morning when you woke up and vomited.

But most of all, I saw it in the way you lay under your khaima, telling me that death doesn’t scare you — that it’s just another journey.

Together we dream of Polynesian beaches, but your sweetest memory is a cappuccino and a croissant at a bar in Ponte Milvio.

“A cream croissant,” you say, “the kind that doesn’t flake — the hard ones, that leave crumbs all over your shirt.”

If you were stronger, you’d open a beach café in Nouakchott and sell those exact croissants. Or maybe, with a camera in hand, you’d show the world how beautiful your home truly is.

That’s what I admire about you: even now, with so much already decided, you haven’t given up. But why choose to settle in the desert, after a life of nomadism? They say people go to the desert to “find themselves.”

But in the sand and stone, you say, you’ve found something else — disorpellamento — a stripping-away. There is nothing left to want. Nothing to regret. Nothing to chase.

And so the desert reveals itself: not as empty, but alive. The songs of the nomads interrupt the silence. Tea is poured. A piece of bread is passed. And a flower blooms — shyly — after all that drought.

You don’t “find yourself” in the desert.

The desert is a mirror. It shows you who you are, and what you won’t change. It shows you what you already know but won’t accept. It shows you what you need — but must fight to reclaim. It reveals the connection with nature and others we’ve long forgotten. It shows us the essential — still alive, still rooted, just hidden beneath a surface layer of noise.

Because the desert is not where you think it is. The Sahara is more alive than a capital city, and the most crowded metropolis is emptied if the essential poles of life are demagnetized.

— Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

We lived together for forty-four days. Sometimes time disappears in a second. Sometimes days stretch out and become unbearably slow, and boredom creeps in. Then I’d come to you, asking endless questions about your past, your future — but never the present.

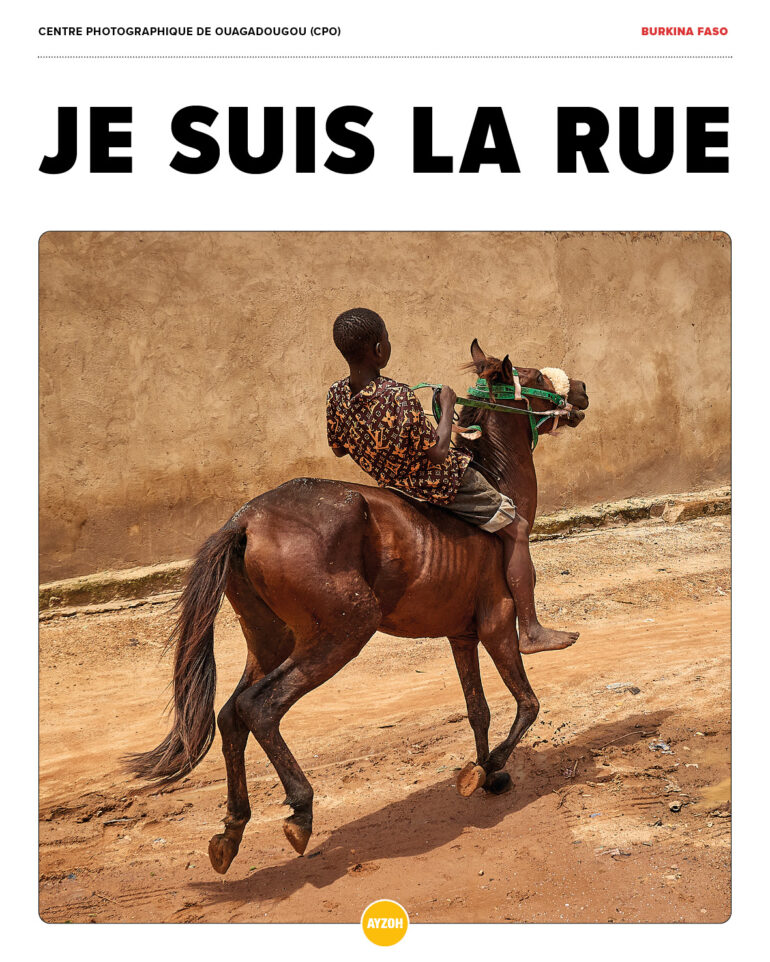

You often think about what your life might’ve been without illness. You think of wine, horses, the lips of a woman who left a deep mark on your heart.

You’ve let go of many things, but not of that “colorless apathy” that seems to define the modern world. The frenzy of life in Europe once tormented you, but now the slowness of Africa has taken hold. You no longer wait impatiently. You just know — things will happen.

In the desert, you feel time pass. Beneath the burning sun, you walk toward evening, toward the cool wind that will refresh your limbs and dry your sweat. Beneath the burning sun, animals and humans alike move toward the great watering hole, with the same certainty with which we all move toward death. And so, laziness is never in vain. Each day becomes as beautiful as the roads that lead to the sea.

— Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

In most people’s imagination, the desert is dry, silent, lifeless. But that’s only because — as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry writes — “it does not give itself to one-day lovers.”

I’ve known a desert that’s green. Alive. Full of sound and color. A place that doesn’t match the narrative of extreme adventure — but instead, a place you can fall for. So deeply, you no longer want to leave.

He will return. Obsessed with his lost nobility, drawn to the place where each step feels like falling in love. He will have believed this was just an adventure, and that the essential waited for him elsewhere. But he will return with horror to discover that the only true wealth he possessed was here, in the desert: the prestige of the sand, the night, the silence, this wind-swept prairie of stars.

— Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Everyone asks: “Don’t you want to go back to Italy?” And you answer, without hesitation: no. You wouldn’t trade the freedom of walking barefoot for anything.

But I can’t stay.

My journey ends here, and it leaves a bitter trace. I’m afraid of the desert I’ll find when I return. I’m afraid of not hearing your voice anymore. You, instead, are calm. You say: “You’ll come back. I know you will.”